Michel de Montaigne, the prolific, French, 16th century essayist, is considered the inventor of the form and what we call it today. Stuart Hampshire, in his introduction to the The Complete Works of Michel de Montaigne (Everyman’s Library), describes Montaigne’s idea “as the loose, unstructured, discursive essay, replete with deliberate irrelevances, antiquarian references and classical quotations, with snippets of autobiography and fragments of philosophy and with speculations about the relations between mind and body.” (p. xvii)

Among the scores of essays Montaigne wrote, while occasionally serving in various government roles, are accounts and commentaries concerning many of his infirmities. Kidney stone attacks in particular plagued Montaigne, and so they became subject matter for several essays. His focus on “the stone,” as he called this condition, generally concerned the physical and mental suffering acute attacks caused him, his work at reconciling a life with intermittent attacks, and from these two features, the profit his attacks afforded him. (N.B. I have drawn Montaigne’s words from the Everyman’s Library collection of Montaigne’s essays.)

Attack of The Stone

Pain from acute kidney stone attacks always ranks amongst the worst humans suffer from diseases, injuries, or various conditions. Montaigne’s vivid and horrifying descriptions of his kidney stone attacks lend credibility to these rankings: “I am at grips with the worst of all maladies, the most sudden, the most painful, the most mortal, and the most irremediable.” (p. 698)

To others looking on during one of his attacks, Montaigne says: “They see you sweat in agony, turn pale, turn red, tremble, vomit your very blood, suffer strange contractions and convulsions, sometimes shed great tears from your eyes, discharge thick, black, and frightful urine…” (p. 1019) No observer could doubt the intensity of pain kidney stone attacks produce after reading Montaigne’s accounts; no current sufferer would contradict them.

A Life Accommodated

The pain and agony kidney stones inflict are never forgotten. And, the fear of knowing they will strike again is ever present, with good reason; they often return time after time. Indeed, this threat is a form of suffering of its own. Montaigne was cognizant of this reality, and writes about how he learned to live with the inevitability of a next attack.

In the eighteen months or thereabouts that I have been in this unpleasant state, I have already learned to adapt myself to it. I am already growing reconciled to this colicky life; I find in it food for consolation and hope. So bewitched are men by their wretched existence, that there is no condition so harsh that they will not accept it to keep alive. (p. 697).

His primary approach was adopting a mentality allowing him to maintain as much function as possible while under frequent sieges of the stone: “I have kept my mind, up to now, in such a state that, provided I can hold fast, I find myself in a considerably better condition of life than a thousand others, who have no fever illness but what they give themselves by the fault of their reasoning.” (p. 701) Montaigne advises these thousand others they would do well to adjust their reasoning because the problem “occupies in us only that much room as we give it.” (p. 47) As for how much room to give the stone, he says, “we have no cause for complaint about illnesses that divide the time fairly with health.” (p. 1020)

With his reconciliation of a life with the stone, Montaigne carries on as close to a normal life as possible and not being obsessed with his condition: “Do not expect me to go and amuse myself testing my pulse and my urine so as to take some bothersome precaution; I shall be in plenty of time when I feel the pain, without prolonging it by the pain of fear.” (p. 1023)

Profitable Kidney Stones

“I have in [my] time become acquainted with the kidney stone through the liberality of the years. Familiarity and long acquaintance with them do not readily pass without some such fruit.” (p. 697) The fruit is the profits he gains with kidney stones. The profits derived mainly from lessening his fear of death, better appreciating the health he had, and getting on with his life more easily. As such he has profited from receiving benefits exceeding the costs he incurred through suffering.

“I’m not dead yet.” Montaigne wrote that when the stone visited him, he felt he was “so far forward into death that it would have been madness to hope, or even to wish, to avoid it, in view of the cruel attacks that this condition brings.” (p. 771) He had come face to face with death on those occasions only to survive. What he gained from these encounters he eventually appreciated as a form of profit.

I have at least this profit from the stone, that it will complete what I have still not been able to accomplish in myself and reconcile and familiarize me completely with death: for the more my illness oppresses and bothers me, the less will death be something for me to fear. (p. 698)

“What a feeling.” The perception of good health is created mostly either by various metrics like physical fitness standards (e.g., weight, strength, endurance), medical diagnoses, and other empiric findings, or by contrasts to states of bad health. Montaigne claimed great profit because his kidney stones reminded him how good his health is generally when he’s not in the midst of an attack.

But is there anything so sweet as that sudden change, when from extreme pain, by the voiding of my stone, I come to recover as if by lightning the beautiful light of health, so free and so full, as happens in our sudden and sharpest attacks of colic? Is there anything in this pain we suffer that can be said to counterbalance the pleasure of such sudden improvement? How much more beautiful health seems to me after the illness, when they are so near and contiguous that I can recognize them in each other’s presence in their proudest array, when they vie with each other, as if to oppose each other squarely! (p. 1021)

Montaigne also perceived profit from the finite nature of kidney stone attacks. He points to the abrupt resolution of an attack followed by a quick return to good health in contrast to other diseases causing their victims continuous suffering: “My sickness has this privilege, that it carries itself clean off, whereas the other always leave some imprint and change for the worse that makes the body susceptible to a new disease.” (p. 1022)

“Brush off the clouds and cheer up.” To Montaigne, kidney stone attacks are gruesome and can make the sufferer wish to die. But, by their nature, and as a form of profit, they can make life better between attacks than it would be otherwise. Montaigne sees this profit in the certainty that any attack will end and lives can go on as planned, because the stone is “a disease in which we have little to guess about. We are freed from the worry into which other diseases cast us by the uncertainty of their causes and conditions and progress—an infinitely painful worry.” (p. 1023) This means for Montaigne, that the stone “almost plays its game by itself and lets me play mine. (p. 1022)

The idea that there can be profit or any form of benefit from having kidney stones is likely preposterous to modern day sufferers, especially when effective analgesics and surgical techniques for acute attacks and methods for preventing them are available. Many people, however, still struggle with chronic kidney stones making Montaigne’s observations and advice relevant yet. Drawing from a cultural analog, he might tell them to look for the profit kidney stones generate, and when found, they will see that gray skies are going to clear up, so put on a happy face. Alas, his admonition would likely be met with stony silence.

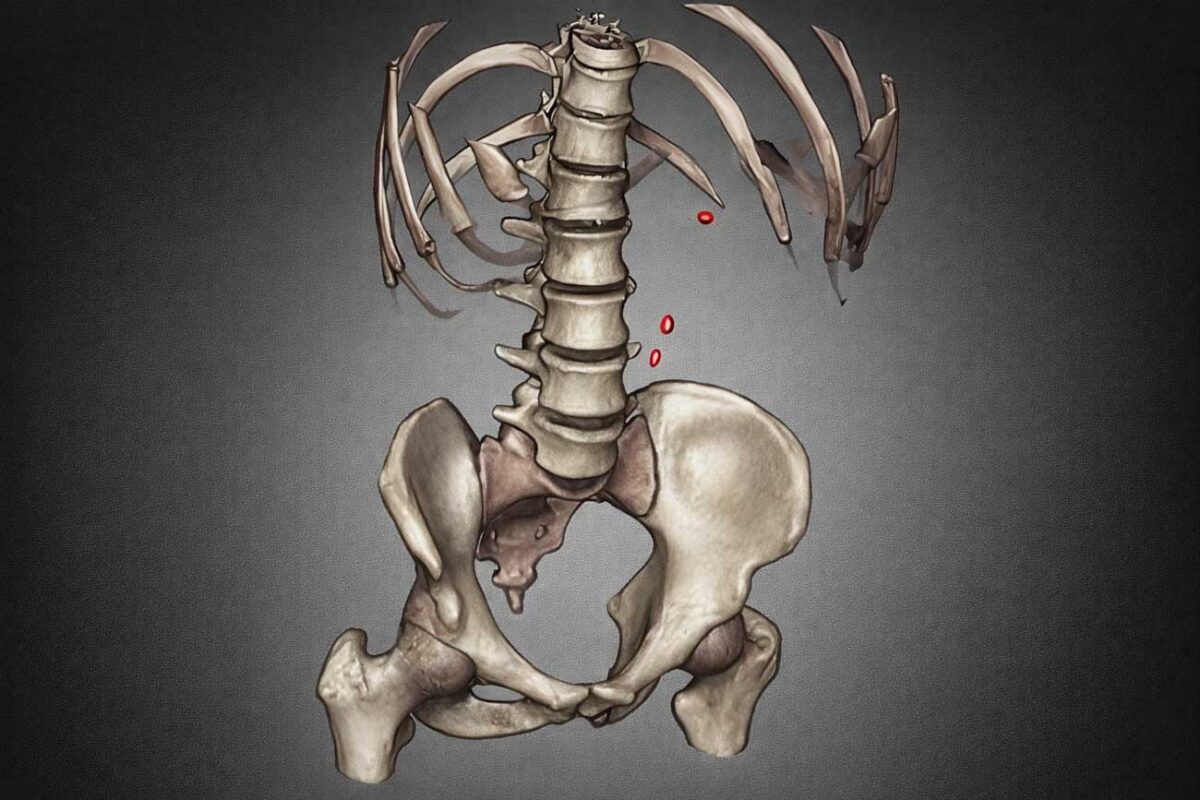

Kidney stone image from the gallery at KidneyStoners.

Title image credit: Three Kidney Stones Highlighted in Red. Sanderlewis, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons