Cultures throughout the world have honored the medical profession for thousands of years, even though, for the most part, effective medications and safe surgical procedures have only been available for the last century. Physicians often attribute their predecessors’ success to the “better than nothing” theory. Historically, doctors provided kindliness, comfort, and emotional support. Often they received the credit when their patients’ natural healing processes resulted in cure. Even in this view, the doctor’s use of language must have been considered powerful. For example, they believed it was unethical to tell a patient that his or her prognosis was grim, or to use certain loaded words, like cancer or consumption, because they assumed the patient would lose hope and, therefore, suffer more. Clearly, words could cause harm. Likewise, doctors believed that cheerful platitudes could help a sick person cope with his or her illness.

Many modern physicians minimize, or are unaware of, a second source of historical medical success: the power of language and ritual to facilitate physical and psychological healing. Assisted by his priests, Aesculapius, the Greek god of medicine, healed the sick through poetry, narrative, and ritual. Even Hippocrates, the father of naturalistic Western medicine, paid tribute to Aesculapius in his famous Oath, and emphasized in many of his case histories the importance of interpersonal and contextual factors in patient care. While the healing power of language and context was rarely explicit in the subsequent history of Western medicine, it finally emerged into consciousness during the last two hundred years, when it was given the name placebo effect. Initially considered a minor aberration in suggestible people, more recently this component of healing has been recognized as an almost universal human facility (or reaction) of varying and sometimes amazing power.

In this essay I present a case study of a traditional healing ceremony in which the therapy consists entirely of language, especially poetry, and the ritual context in which the language is spoken and chanted. I argue that this is a very powerful example of contextual healing. I then examine our contemporary understanding of the placebo effect, which is also a form of contextual healing, albeit ordinarily much less striking and more “dilute” than the Navajo example. Finally, I comment briefly on some features of healing miracles in the Catholic Church, arguing that these, too, are powerful instances of contextual healing that suggest at their upper limit, so to speak, such mechanisms may actually be able to reverse disease processes, like cancer or neurological impairment. Of course, this outcome is rare, unpredictable, and not at all understood.

Sarah Mailcarrier and the Night Way

Dark cloud is at the door.

The trail out of it is dark cloud.

The zigzag lightning stands high upon it.

An offering I make.

Restore my feet for me.

Restore my legs for me.

Restore my body for me.

Restore my mind for me.

Restore my voice for me.

This very day take out your spell for me.

Happily, I recover.

Happily my interior becomes cool.

Happily I go forth.

My interior feeling cool, may I walk.

No longer sore, may I walk.

Impervious to pain, may I walk.

With lively feelings may I walk.

As it used to be long ago, may I walk.1

These lines constitute a small segment from one of the poems chanted during the Night Way, a nine-day Navajo healing ceremony. In the early 1970s, Sarah Mailcarrier was the matriarch of an extended family whose camp was at Cornfields in Beautiful Valley near Klagetoh Mesa. A healthy woman well into her 60s, she developed severe lower abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, poor appetite, and swelling of her legs over a period of two to three months. Her family took her to Fort Defiance Indian Hospital, some 50 miles from home, where she was discovered to be suffering from cancer of the cervix, which had spread widely, blocking lymphatic ducts in her legs and partially obstructing her kidneys. The recommended treatment was palliative radiation at Gallup Indian Medical Center, a larger hospital in Gallup, New Mexico, another 30 miles distant from Cornfields. Sarah and her family declined this option and, instead, consulted a hand trembler, who diagnosed her problem and recommended a Night Way Sing or healing ceremony. The family hired a ha’a’tali or traditional healer who, along with his assistants, conducted the ceremony over nine days and nights at her camp in Cornfields.2

According to Navajo diagnostic taxonomy, Sarah had fallen out of harmony with the cosmic narrative that defines the proper relationships among the Earth Surface People, the Holy People, and the natural world. This likely was the result of certain traumatic exposures and events in her life. Healing would require restoration of harmony through the chants, rituals, images, and stories that the Holy People had given to the Navajo for just this purpose. The ceremony was successful. Sarah’s symptoms were relieved, her energy restored, her anxiety disappeared, and she continued to function in her role as matriarch for several months until she drifted into a long sleep and died.

To explore the nature of Sarah’s healing, I have to explain a little more about Navajo medical beliefs. In traditional Navajo thought, all illness represents disharmony, in essence a snag or gap in the interconnectedness that characterizes the dineh (people), the harmonious Navajo Way. While there are many causes of disharmony (e.g. witchcraft, demon possession, soul loss, taboo violation, and traumatic exposure, as with Sarah Mailcarrier), the goal of treatment is always the same—to restore proper harmony at all levels, from within the patient’s own heart, to his or her relationship to the cosmos.

The ceremonies, which can last up to nine days, require the patient and family to hire an ha’a’tali and his assistants, and to invite friends and clan members to set aside their other responsibilities and participate in songs, dances, prayers, and other rituals appropriate to the ceremony. Sung by the ha’a’tali these are magnificent narrative poems that tell of the creation of the Navajo people, and how all things were originally placed into their proper order. Likewise, in ceremonial dances, men impersonate Yei Be Chai, intermediaries between the Holy People (whom we might call “gods”) and the Earth Surface People (us), and channel their healing power.

However, the dineh have never rejected Western medicine. Instead, they have integrated Western physicians, clinics, and hospitals into their overall worldview, considering them synergistic with, rather than antagonistic to, traditional ceremonies. The dineh believe that Western health care has simply added a different set of stories and a different network of ceremonies (e.g. clinic visits, x-rays, penicillin shots, arthritis pills) onto their already existing—and far more important—traditional healing practices. The Navajo were quick to observe that bilighani treatments were effective in alleviating outward manifestations, or what we would call symptoms, of disharmony, but they also maintained that such treatments had no influence on the underlying existential disorder. In other words, penicillin shots and arthritis pills are only symptomatic treatments. While bilighani methods could make the fever or rash or cough disappear, at least for a time, the fundamental issue of disharmony would remain. Why me? What does this illness mean in my life? How does this illness reflect my relationship to the cosmos? These questions could only be answered with reference, for example, to the story of Spider Woman, or the Hero Twins, or other narratives of Navajo cosmogony.

Returning to Sarah Mailcarrier, it appears that by undergoing a Night Way Sing, she experienced a dramatic improvement in her quality of life. From a Western perspective, why might this be the case? First, the lengthy ceremony provided extensive and intense social support, represented by the participation of her extended family and friends, their contributions of time and money3, and overall solidarity. An extensive body of research indicates that high level of social support and prosocial behavior are associated with longer life, less morbidity, less disability, and greater satisfaction. Second, Sings are integral components of religious practice. For a person like Sarah Mailcarrier, religious belief (in the Western sense of the term) and cultural practices were inextricable. Once again, considerable research indicates that frequency and intensity of religious practice is associated with the same positive outcomes. Third, the ritual chants, vivid poetic images, storytelling, sandpainting, and dancing of the Night Way embody a belief system that generates positive expectations—and restores coherence to the patient’s life.4

These components—social support, core beliefs, and positive expectations—all rely on language and communication. Empathy, the human ability to “intuit” what another person is thinking or feeling5, is a more basic neurological property than language, but without language humans could not have created the rich symbolic world in which we live. In the 1980s the psychiatrist Donald Sandler distinguished between Navajo symbolic healing, based on an integrated cultural narrative, including symbol and ritual; and scientific healing, which he believed could be clearly distinguished from the latter and which relies solely on specific instrumental effects of drugs, surgery, and so forth.6 Like Sandler, today’s physicians are quite willing to make allowances for the beliefs of patients from other cultures, but at the same time they cling to the belief that scientific medicine transcends culture and our effectiveness as healers is solely, or almost solely, explained by the instrumental effects of drugs and procedures. Thus, there is a widespread belief that scientific medicine is, as a system of curing disease, intrinsically culture-free. Antibiotics kill bacteria whether the patient is a middle-class American or an Amazonian Indian. Culture may enter into the picture for the Indian, e.g. because of his mistaken beliefs about illness, but has no effect on the American, whose beliefs (whatever they are) are medically invisible.

From Placebo Effect to Contextual Healing

For over 200 years Western physicians have been explicitly aware of the so-called placebo effect, but for most of that time have considered it a minor and somewhat disreputable factor on the medical scene. The first person to recognize and demonstrate the placebo effect was English physician John Haygarth in 1799, who was curious about the purported benefit a popular medical treatment of his time called “Perkins tractors,” metal pointers supposedly able to ‘draw out’ disease from the patient’s body. They were sold at the extremely high price of five guineas, and Haygarth set out to show that the high cost was unnecessary. He did this by comparing the beneficial results obtained by using dummy wooden tractors with those obtained with a set of allegedly active metal tractors. There was no difference. He published his findings in a book called On the Imagination as a Cause & as a Cure of Disorders of the Body.7 Subsequently, the term placebo (“I will please”) was coined to mean, as in this 1811 definition, “an epithet given to any medicine adopted more to please than to benefit the patient.”

The modern understanding of the power of placebo intervention probably originated with Henry K. Beecher‘s 1955 classic paper, “The Powerful Placebo,” in which he described his experience as a medic during World War II8 After running out of pain-killing morphine, in desperation he replaced it with a simple saline solution, while continuing to tell the wounded soldiers that the injection was morphine. He often found that saline appeared to be almost as effective as morphine in relieving his patients’ pain and anxiety. Despite this dramatic demonstration, the orthodoxy surrounding placebo effects for the next several decades came to include three major components:

- A focus on the specific intervention as its cause, i.e. the pill or the procedure itself “carried” or “transmitted” the placebo effect.

- Importance of patient vulnerability, i.e. only suggestible persons were placebo-responders.

- Miscommunication, i.e. the patient must deceived, directly or indirectly, into believing that he or she was receiving an “active” treatment.

However, research in the last 30 years has completely exploded this orthodoxy and replaced it with a much more complex understanding that sheds light, for example, on the power of traditional medical systems, like the Navajo, that rely on poetry, narrative, and ritual to heal. To quote Franklin Miller and Ted Kaptchuk, two of today’s most prominent investigators in the field: “To promote a more accurate understanding of the elusive and confusing phenomenon known as the placebo effect, we suggest that it should be reconceptualized as contextual healing… Factors that may play a role in contextual healing include the environment of the clinical setting, cognitive and affective communication of clinicians, and the ritual of administering treatment.”9 Elsewhere, Kaptchuk added, “Research also suggests that (narrative and) ritual healing not only represents changes in affect, self-awareness, and self-appraisal of behavioral capacities, but involves modulations of symptoms through neurobiological mechanisms.”10

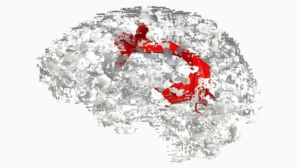

Contextual healing, as the term implies, occurs in the context of expectations that arise from a network of beliefs. Moerman and Jonas, highlighting the fact that context can communicate therapeutic meaning to the patient, prefer using the term “meaning response.”11 In some cases these beliefs may be based on past experience, but isolated from, or not intimately connected to, deeply meaningful worldviews (e.g. that penicillin cures a sore throat). In other cases they may closely connected to robust belief systems about the nature and origin of illness and healing (e.g. the Navajo Night Way). The latter are obviously more important than the former. The net valence of one’s beliefs determines the meaning of any medical interaction or treatment and, therefore, one’s expectations of its effect. Language, communication, empathy, narrative, and ritual determine the healing context. The universality of contextual effects on symptom relief has been demonstrated convincingly in neurobiological studies, especially those dealing with pain reduction. For example, on fMRI “placebo” treatment reduces activation of pain-related areas of the brain, e.g. the dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex.12, 13

Contemporary research on contextual healing has also revealed a number of unexpected features that are inconsistent with the earlier orthodoxy regarding placebo effects. For example,

- Placebo effectiveness does not require deception; patients may report relief of symptoms even when told they are receiving placebo treatment.14

- There may be a link between genetic variants in the dopamine, opioid, serotonin, and endocannabinoid pathways in the brain and placebo responsiveness.15

- Placebo effects (as well as nocebo, or harmful effects) can exist in routine clinical practice, even if no “intervention” is given.16, 17

- Placebo response is greater when observed in clinical practice than when measured in randomized clinical trials.8, 19

This last feature requires some clarification. This is precisely the opposite of specific medication effects, which are almost always more prominent in clinical trials than in routine practice because the populations in trials are highly homogenized (e.g. limited age range, selected to exclude co-morbidities), adhere to highly structured protocols (e.g. frequent follow-up, expert clinicians. methods to insure, or at least measure, compliance) and include only highly motivated subjects. These conditions are ideal for demonstrating the drug’s maximal specific benefit (efficacy), while at the same time somewhat less ideal for showing contextual healing power, since individual variation and personal narrative are minimized. The specify potency of a drug tends to be less in ordinary clinical practice (effectiveness) where there are a mixture of patients with different ages, backgrounds, comorbidities, and levels of compliance. However, the latter less-than-standardized conditions are likely to enhance the power of contextual healing. For example, “It seems likely that the effectiveness of placebo for pain relief in osteoarthritis can be considerably larger than its efficacy. The artificial conditions of a clinical trial constrain the extent to which context effects…” can be manifested.20

Can Language Spoken in Context Cure Disease?

Given that contextual or narrative healing may be a powerful force in relieving symptoms and improving quality of life, can it ever cure chronic or progressive disease? It is unlikely that Sarah Mailcarrier’s Night Way ceremony damaged her cancer cells or had any influence on their progress. However, it seems clear that narrative healing may in many cases “cure” at least some cases of major depression, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress syndrome, substance abuse, and perhaps even schizophrenia. Since these disorders are all characterized by abnormal concentrations or function of neurotransmitters, it is safe to say that contextual healing influences brain chemistry. Likewise, fMRI studies have shown that placebo treatments alter brain function. For example, placebo treatment in Parkinson’s disease may result in demonstrable changes in imaging, primarily resulting from increased dopamine release in certain areas of the basal ganglia.21 These changes may be associated with improvements in patient function. Likewise, placebo has also been shown to modulate physiological processes, like lowering blood sugar in diabetics and treatment enhancing immune responses, which may be related to neurophysiology in complex ways. 22, 23

There is a long history of rare, unexplained, but yet well-documented, cures in medicine. As medical knowledge has increased, the number of such inexplicable or “miracle” cures has diminished. Nonetheless, instances of the disappearance of widely metastatic cancer, or the resolution of aggressive autoimmune disease, do occur. Religious persons attribute these unexplained cures to supernatural intervention. Jacalyn Duffin’s 2009 book Medical Miracles: Doctors, Saints and Healing in the Modern World describes her investigation in the Vatican archives of 1400 cases of miracle cures that were cited as evidence in canonization proceedings between 1588 and 1999.24 Of these, 503 cases occurred in the 20th century and 220 of them between 1975 and 1999, the final year of her study. Most in the 1975-1999 group were extremely well-documented. 20th century cures included 41 cases of cancer or leukemia, 109 neurological diseases (e.g. multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, Parkinson’s disease), and 89 obvious orthopedic conditions. The unifying factor was that every “miracle” was associated with narrative and ritual. Prayer to Jesus, Mary, or another person, i.e. the candidate for sainthood, took place in various contexts, solitary or communal narrative associated with Masses, novenas, relics, monuments, tombs, etc. These features are all analogous to Navajo healing ceremonies. The same sort of analysis has been applied to “miracle” cures at Lourdes, a pilgrimage site in France, with similar results: a relatively small number of thoroughly documented and inexplicable cures among many thousands of claims.25

A Note on Nocebo

Traditional cultures also recognize the power of language to harm, as well as heal. This includes spells, hexes, curses, and similar verbal insults that produce harmful effects on the person to whom they are directed. Since the phenomenon of “Voodoo death” was described by Cannon in 194226, various other syndromes of illness and death based on witchcraft and curses were re-evaluated or newly described have been reported; for example, “bone-pointing” (kurdaitcha) in Australia and “breaking tapu” in New Zealand. Among Aboriginal people an individual targeted by bone pointing may die within 24 hours or may decline inexorably over a period of days. 27 Such a curse can only be reversed by the intervention of an appropriate sorcerer. Among the Navajo, many serious illnesses are caused by curses that lead to “soul loss” or “possession.”

Likewise, in Western medicine the words of physicians or other health care professionals, and the context in which they are spoken, may actually increase a patient’s symptoms, anxiety, and suffering. The eminent internist Eric Cassell, paraphrasing an old childhood chant, taught “Sticks and stones may break your bones, but a word can kill you.” (Personal communication) There is no room here to discuss nocebo-inducing language in medical practice, which is analyzed in detail in chapter 13 of Coulehan and Block.28, 29

Conclusion

In this essay I make the claim that contextual healing (aka the placebo effect) plays a major role in medical practice and that language, either spoken verbally, or used internally to represent beliefs and personal meanings, is the carrier or operative agent of contextual healing. In most circumstances contextual healing has a limited, but clinically significant, range of effects. The clinician by employing “skillful means” (to use a Buddhist expression) can promote and enhance contextual healing in the clinical setting.20, 31 Navajo medicine is an example of a traditional medical system built almost entirely on exploiting the vast resources available to contextual healing. To a greater or lesser extent, Curanderismo, Vodun, homeopathy, Christian Science, and many other approaches to the treatment of illness are based on contextual healing. The upper limit of this healing power is normally modest, but under certain circumstances for certain people it may be quite spectacular, as in presumptive miracle cures.

Notes

- Navajo Night Way Song, https://www.lindavallejo.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Chants-Prayers-Poems-2011-2.pdf, accessed on 3 December 2025.

- Coulehan J. May I Walk in Beauty. Humane Medicine, 1992; 8: 65-69.

- Kaptchuk TJ. Placebo studies and ritual theory: a comparative analysis of Navajo, acupuncture and biomedical healing. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2011; 366: 1849-1858

- By “intuit” I mean the development of a theory of mind (i.e. others have minds just like me). Primates and perhaps some other mammals have an analogous ability, but presumably without a symbolic language.

- A Sing is expensive. The patient’s family must hire an ha’a’tali and his assistants and also provide food and drink for a large number of participants and attendees. Some participants must also take time off from their jobs or other pursuits for several days.

- Haygarth J MD. On the Imagination as a Cause & as a Cure of Disorders of the Body, Bath; R. Cruttwell, 1801.

- Sandler D. Navaho Symbols of Healing. New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979, pp. 265-273.

- Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. JAMA. 1955;159(17):1602-1606

- Miller FG, Kaptchuk TJ. The power of context: reconceptualizing the placebo effect. JRSM. 2008; 101: 222-225, p. 223.

- Kaptchuk TJ. Placebo studies and ritual theory: a comparative analysis of Navajo, acupuncture and biomedical healing. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011; 366: 1849-1858, p. 1849.

- Moerman DE, Jonas WB. Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Ann Intern Med 2002; 471-476.

- Brody H, Miller FG. Lessons from recent research about the placebo effect—from art to science. JAMA 2011; 306 (23): 2612-2613

- Colagiuri B, Schenk LA, Kessler MD, Dorsey SG, Colloca L. The placebo effect: From concepts to genes. Neuroscience. 2015; 307: 171-190

- Pecina M, Zubieta JK. Molecular mechanisms of placebo responses in humans. Mol Psychiatry. 2015; 20: 416-423

- Miller FG, Coilloca L, Kaptchuk TJ. The placebo effect: illness and interpersonal healing. Perspect Biol Med. 2009; 52: 518

- Stub T, Foss N, Liodden I. “Placebo effect is probably what we refer to as patient healing power”: a qualitative pilot study examining how Norwegian complementary therapists reflect on their practice, BMC Complementary and Alternative Med. 2017; 17:262

- Benedetti F, Pollo A, Lopiana L, Lanotte M, Vighetti S, Rainero I. Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 4315-4323

- Dieppe P, Goldingay S, Greville-Harris M. The power and value of placebo and nocebo in painful osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2016; 24:1850-1857

- Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C et al. German acupuncture trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167: 1892-1898

- Dieppe et al, p. 1852.

- Fuente-Fernandez R, Ruth TJ, Sossi V, Schulzer M, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Expectation and Dopamine Release: Mechanism of the Placebo Effect in Parkinson’s Disease. Science. 2001; 293: 1164-1166.

- Skvortsova A, Veldhuijzen DS, van Dillen LF, Zech H, Derkson SM, Sars RH, Meijer OC, Pijl H, Evers AWM. Influencing the Insulin System by Placebo Effects in Patients With Diabetes Type 2 and Healthy Controls: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2023; 85: 551-560

- Smits RM et al. The role of placebo effects in immune-related conditions: mechanisms and clinical considerations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018; 14(9): 761-770.

- Duffin J. Medical Miracles. Doctors, Saints, and Healing in the Modern World. New York, Oxford University Press, 2009.

- François B, Sternberg EM, Fee E. The Lourdes medical cures revisited. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2014 Jan;69(1):135-62.

- Cannon WB. “Voodoo” death. American Anthropologist, 1942; 44: 169-181. Reprinted in Am J Public Health. 2002; 92 (10): 1593-1596.

- Spencer, Baldwin; Gillen, F.J. Native Tribes of Central Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2010 [1899], pp. 476–477.

- Coulehan J, Block M. The Medical Interview. Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, F.A. Davis Company, 5th edition, 2006, pp. 21-44 and 249-278.

- Hansen E, Zech N. Nocebo effects and negative suggestions in daily clinical practice – forms, impact and approaches to avoid them. Front Pharmacol. 2019 Feb 13; 10:77.

- Coulehan J, Clary P. Healing the healer: Poetry in Palliative Care, J Palliative Medicine, 2005; 8: 382-389.

- Blasini M, Peiris N, Wright T, Colloca L The role of patient-practitioner relationships in placebo and nocebo phenomena. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2018; 139:211-231.

Web image created by Medhum.org