“’She’s got…the pestilence,’ Hamnet whispers. ‘Hasn’t she? Mamma? Hasn’t she? That’s what you think, isn’t it?’” Yes, that is what Hamnet’s mother, Agnes, thinks; her eleven-year-old daughter Judith, Hamnet’s twin sister, is stricken by the plague. She sees “the swelling at Judith’s neck. The size of a hen’s egg, newly laid…There are other eggs, forming in her armpits, some small, some large and hideous, bulbous, straining at the skin.” (p. 105) These are telltale signs people of Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England in 1596 would recognize but hope they never see.

Hours later, after she has tried all the methods known to her, Agnes is asleep next to Judith’s pallet. Hamnet, overwrought that he is about to lose the “other side to him,” crawls from his pallet to Judith’s side, beginning to feel poorly also. He arranges himself next to Judith in a way that made it almost impossible for people to tell them apart, hoping as Death came to take her, it would be fooled into taking him instead. “And if either of them is to live, it must be her. He wills it. He grips it…He, Hamnet, decrees it. It shall be.” (p. 169)

When Agnes awakens, she eventually discerns that “her daughter has been spared…but, in exchange, it seems that Hamnet may be taken.” (p. 208) She reinitiates the treatments she had tried on Judith, but nothing works. Hamnet takes his last breath. Agnes wonders how she could have saved him, how she could have missed Hamnet being at risk before she is able to comprehend: “he is dead, he is dead, he is dead.” (p. 219)

From this event on, O’Farrell constructs the trajectory of the family’s grief with a particular focus on Agnes. Her grief is amplified by resentment and incredulousness over her husband’s return to London soon after the burial because he feared his work as an actor and playwright would lose irretrievable ground with a prolonged absence. These emotions and grievances reach a crescendo over a period of years before understandings are reached and catharsis experienced.

The Plague Comes for the Twins

Easily lost in the gripping story O’Farrell tells and the emotional torrents she evokes is the chapter explaining how the plague reached the twins. She takes the modern-day, biomedical understanding of the complex chain of events involved in the spread of plague and weaves it into how she imagines it could happen amidst everyday life in the countryside outside London during the 1590s.

A basic biomedical reference O’Farrell could have consulted in piecing together a credible sequence of events leading to the twins’ infections would likely include the same details provided in a summary of plague spread published in the 2021 volume of the American Journal of Medicine*:

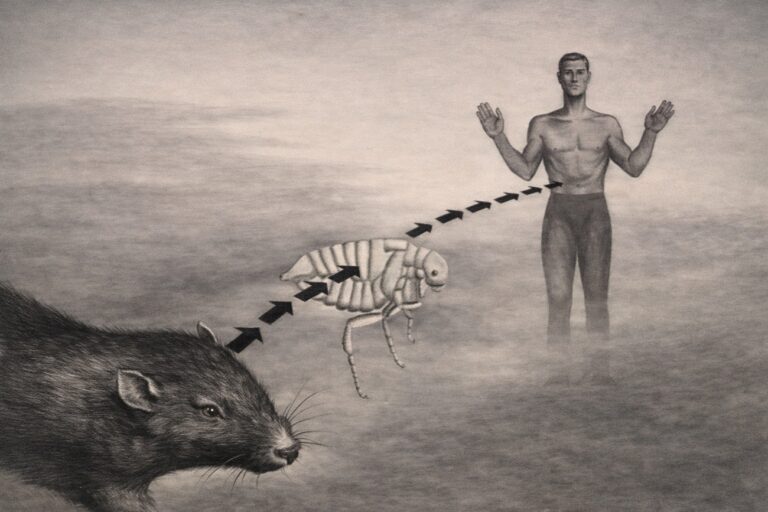

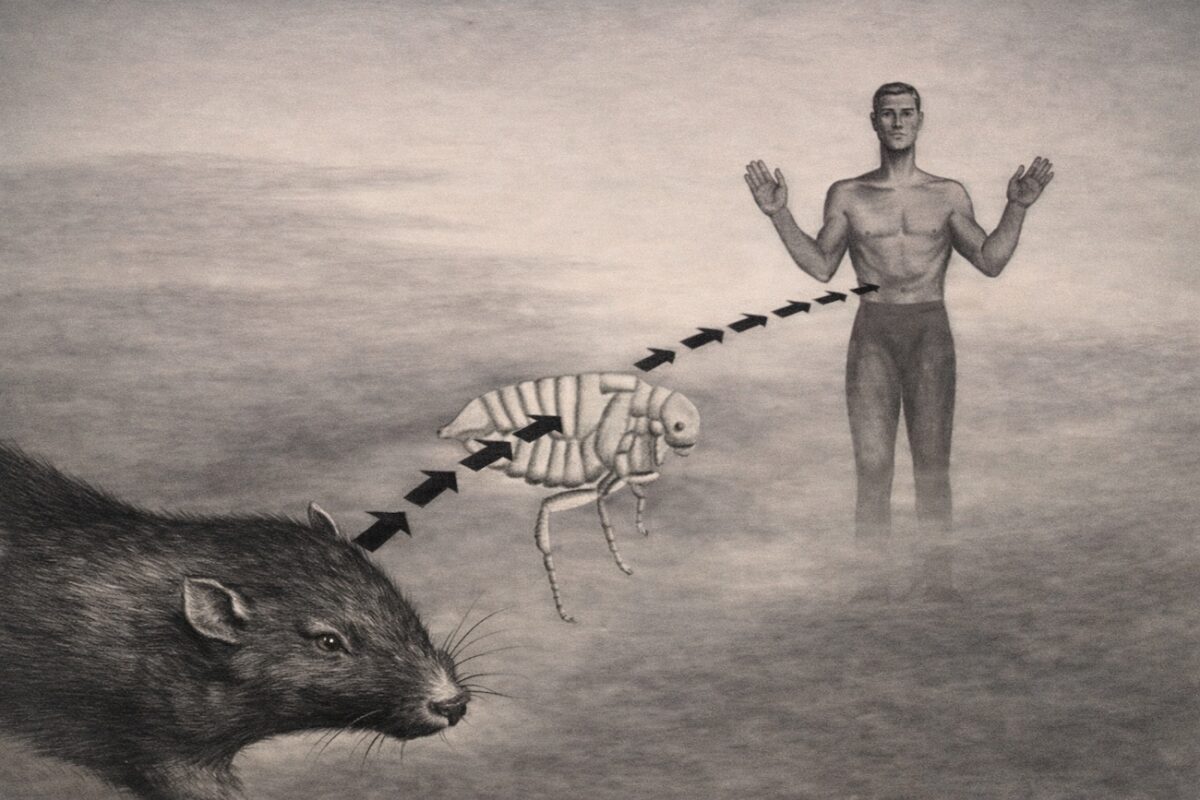

An ancient disease, its bacterial agent (Yersinia pestis) is an aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus in the family Enterobacteriaceae. Its primary vector for transmission is the Xenopsylla cheopis flea, although roughly 80 species of fleas can carry it. During the Black Death, the flea was transported by the black rat or Rattus. A controversial new theory argues that ectoparasites such as human fleas and lice also spread the disease during the second plague pandemic [1347-1665]. Fleas can also survive in infected clothing or grain. The bacteria multiply in infected rodents and block the fleas’ alimentary canal, causing the fleas to regurgitate the Y. pestis bacteria into its animal host…Plague transmission is generally from infected fleas by rodent vectors or, rarely, in clothing or grain but may also occur through ingesting contaminated animals, physical contact with infected victims, or direct inhalation of infectious respiratory droplets.

O’Farrell could also find plenty of well-researched historical accounts of the plague impacts at the time and place she set the novel. The plague affecting Stratford then is thought to have first entered England in 1348 from ships docking in cities along the southwestern coastline. England struggled with it almost constantly for more than 300 years until it dissipated after 1665. From this biomedical and historical background, O’Farrell created a realistic framework for the story, and a reasonable representation of the all the factors needed for the infection to find the twins in 1596 Stratford.

She starts her explanation of how the twins got infected by specifying that,

two events need to occur in the lives of two separate people, and then these people need to meet. The first is a glassmaker on the island of Murano in the principality of Venice; the second is a cabin boy on a merchant ship sailing for Alexandria on an unseasonably warm morning with an easterly wind. (p. 140)

The glassmaker is filling an order for decorative glass beads received from a dress shop in Stratford, England. But, because of a recent hand injury, a fellow worker is given the job of packing the order. This worker doesn’t know that the glassmaker “usually pads and packs the beads with wood shavings and sand to prevent breakage. He grabs instead a handful of rags from the glassworks floor and tucks them in and around the beads.” (pp. 140-141).

Meanwhile, the merchant ship has docked in Alexandria, and the cabin boy has been sent ashore for provisions. He quickly encounters a man with a monkey, and the monkey quickly jumps on the cabin boy, and then all over the boy, passing along three infected fleas. One of them accompanies the boy back onboard ensconced “in the fold of the red cloth tied around the boy’s neck, given to him by his sweetheart at home.” (p. 144) The flea doesn’t stay there long. It jumps into the fur of one of the ship’s cats the boy picks up and nuzzles. Soon after the cat is sickened by its passenger and seeks comfort on the hammock of a midshipman, who upon approaching his hammock for a night’s sleep, finds a dead cat. The flea, now needing a new place to live “makes its way, by springing and leaping, to the fecund and damp armpit of the sleeping, snoring midshipman, there to gorge itself on rich, alcohol-laced sailor blood.” (p. 144) Three days later, the midshipman is dead.

The ship arrives in Murano to pick up cargo including the glass beads. The cabin boy and the glassmaker come eye to eye as the glass beads are loaded onto the ship. And at that moment, the monkey flea, which had found a way back to the boy after time with some of the ship’s rats and its chef, leaped onto the glassmaker. He and many others in his factory subsequently succumb to “a mysterious and virulent fever.” (p. 149)

In the hold of the ship now heading to England, the progeny of the monkey flea leap from dying rats to cats lying on top of the boxes filled with the glass beads until the cats die. The fleas eventually “crawl down into these boxes and take up residence in the rags padding the hundreds of tiny, multi-coloured millefiori beads (the same rags put there by the fellow worker of the master glassmaker…)”. (p. 148) The ship arrives in London and the boxes of glass beads are taken to a wharfhouse where they are stored for about a month before picked up for further transport.

O’Farrell ends her tale of how the plague found the twins through the delivery of the box with infected fleas to their final destination. The box of beads “still wrapped in rags from the floor of the Venetian glassworks” is transported to an inn located near the northern reaches of London. (p. 149) Then, a messenger collects the box and takes them by horseback on a two-day journey to another inn near Stratford. O’Farrell adds how during this ride the mass of infectious plague vectors and organisms intensifies.

The fleas in the rags crawl out, hungry and depleted by their hostless stay in the wharfhouse. Soon, however, they are recovered, rejuvenated, springing from horse to man and back again, then out on to the various people the rider encounters along the way…By the time the rider reaches Stratford, the fleas have laid eggs: in the seams of his doublet, in the mane of the horse, in the stitching of the saddle, in the filigree and weave of the lace, in the rags surrounding the beads. These eggs are the great-grandchildren of the monkey flea.

The box with the beads and the fleas is now in the town where the twins live. An innkeeper there has it, and gives a boy a penny to deliver the box to the dress shop that ordered it many months before. The fleas have found Hamnet.

Judith is at the dress shop helping out when the box is delivered.

The seamstress holds aloft the box. ‘Look,’ she says to the girl, who is small for her age, and fair as an angel, with a nature to match.

The girl clasps her hands together. ‘The beads from Venice? Are they here?’

The seamstress laughs. ‘I believe so.’

‘Can I look? Can I see? I cannot wait.’

The seamstress puts the box in her counter. ‘You may do more than that. You may be the one to open them. You’ll need to cut away all these nasty old rags. Take up the scissors there.’

She hands the girl the box of millefiori beads and Judith takes it, her hands eager and quick, her face lit with a smile. (pp. 150-151)

The fleas have found Judith.

When Literary Narrative Serves as Biomedical Text

O’Farrell’s narrative, fictional model of plague spread embedded in her story imagining what could have caused the death of an eleven-year-old boy in 1596 takes into account both the virulence of the infection and the many and varied ways it can spread. To make that point, she, much as would any epidemiologist, tells of others killed as the fleas made their way from Murano to Stratford, such as workers in the glassmaker’s factory, midshipmen on the boat, and various people encountering land-based messengers carrying the box of beads to those awaiting it. In that way, her model also explains how the mortality estimates of one-tenth to one-third of the populations from frequent plague visitations over three centuries could be generated.

O’Farrell could have left this part out of the novel without losing much of the core storyline or emotion and drama of it. Indeed, the movie version gives it only a few seconds of attention showing the twins’ father walking by a street puppet show during a scene representing the spread of and death from plague delivered from a ship. By including the chapter, however, O’Farrell compounds the drama and emotion, and reveals the complexities involved in our fates.

And, as I recall the drudgery of reading and mastering the intricacies of infectious disease spread and pathology such as those of bubonic plague, I wish I had O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet at the time. The experience would have been enjoyable and memorable where the experience with biomedical texts were not in either way. Perhaps this application was not in O’Farrell’s mind for the book, but it could go a long way in ridding us of the plague of turgid, mind-numbing, and indecipherable biomedical prose. Whether or not she knows it, O’Farrell has in this novel brought attention to a plague of another house.

Hamnet

Maggie O’Farrell

Alfred A Knopf; 2020

*From: Glatter JA, Finkelman P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. American Journal of Medicine 2021; 134(2): 176–181.

Image Credits

The path of infection of plague from rats via fleas to man, by A.L. Tarter from the Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

A rat on board a ship, carrying the plague further afield, by A.L. Tarter from the Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The word plague hovers above a victim’s face, by A.L. Tarter from the Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)