The Case of the 1918 Flu Pandemic

Commonly argued among readers is whether fiction or nonfiction brings the most value to understanding any particular issue. These arguments sometimes end with one interlocutor saying, “I only read nonfiction,” and the other saying, “I only read fiction.” Choosing either one alone, however, can deprive readers of valuable knowledge and perspectives that only both together can provide. Such is the case when reading Laura Spinny’s history, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, and Kathryn Anne Porter’s “short novel”—as she insisted it be called—Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Spinny researches the effects the pandemic had on exposed populations and Porter conjures the effects it had on infected individuals.

The titles for both Spiney’s book and Porter’s story draw from the the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the Book of Revelation (6:8) in the New Testament, and one of the horsemen in particular.

And I looked, and behold, a pale horse! And its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed him. And they were given authority over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword and with famine and with pestilence and by wild beasts of the earth.

Both books speak of death, not as the natural course of human life, but resulting from an apocalypse of a biblical scale, of a vengeful god, and of a plague in form. Spinney applies the apocalypse metaphor to peoples and Porter to persons.

Spinny’s account focuses on how the 1918 flu pandemic altered history.

The flu resculpted human populations more radically than anything since the Black Death. It influenced the course of the First World War and, arguably, contributed to the Second. It pushed India closer to independence, South Africa to Apartheid, and Switzerland to the brink of civil war. (p. 8)

She also describes how national public health and global health organizations reorganized and generated momentum towards today’s more sophisticated agencies. She suggests further that the flu pandemic affected literature and art as well, and speculates about why it’s not remembered in any way like the two world wars of the same century. The bulk of the book, though, describes what happened to populations, and how this pandemic could be considered an apocalypse.

The number of dead could have been as high as 100 million—a number so big and so round that it seems to glide past any notion of human suffering without even snagging on it. It’s not possible to imagine the mystery contained within that train of zeroes. All we can do is compare it to other trains of zeroes—notably, the death tolls of the First and Second World Wars—and by reducing the problem to one of maths, conclude that it might have been the greatest demographic disaster of the twentieth century, possibly of any century.(p. 171)

This is where Porter’s literary contribution to capturing “any notion of human suffering” comes in—the personal apocalypse. Based to a degree on her own experience surviving a case of the 1918 flu, her short novel follows Miranda, a reporter for a local newspaper in Denver, Colorado, during a time when she is early in a courtship with Adam, a soldier on leave from camp but who is soon to be shipped overseas to the battlegrounds of WWI. Together they start to see the flu engulf the area.

“I wonder,” said Miranda. “How did you manage to get an extension of leave?”

“They just gave it,” said Adam, for no reason. The men are dying like flies out there, anyway. This funny new disease. Simply knocks you into a cocked hat.”

“It seems to be a plague,” said Miranda, “something out of the Middle Ages. Did you ever see so many funerals, ever?” (p. 281)

Then, the flu engulfs Miranda, and Porter helps us imagine what a personal apocalypse could be like when an individual succumbs to it. She imagines the Pale Rider pulling her away from her physical moorings on Earth.

I must give up, I can’t hold out any longer. There was only that pain, only that room, and only Adam. There were no longer any multiple planes of living, no tough filaments of memory and hope pulling taut backwards and forwards holding her upright between them. There was only this one moment and it was a dream of time, and Adam’s face, very near hers, eyes still and intent, was a shadow, and there was to be nothing more… (p. 304)

Eventually the Pale Rider tries to pull her away from even any vestige of her corporeal being itself, and were it for a mere particle of life force would have done just that.

Silenced she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely withdrawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence; all notions of the mind, the reasonable inquiries of doubt, all ties of blood and the desires of the heart, dissolved and fell away from her, and there remained of her only a minute fiercely burning particle of being that knew itself alone, that relied upon nothing beyond itself for its strength; not susceptible to any appeal or inducement, being itself composed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live. This fiery motionless particle set itself unaided to resist destruction, to survive and to be in its own madness of being, motiveless and planes beyond the one essential end. Trust me, the hard unwinking angry point of light said. Trust me. I stay. (p. 311)

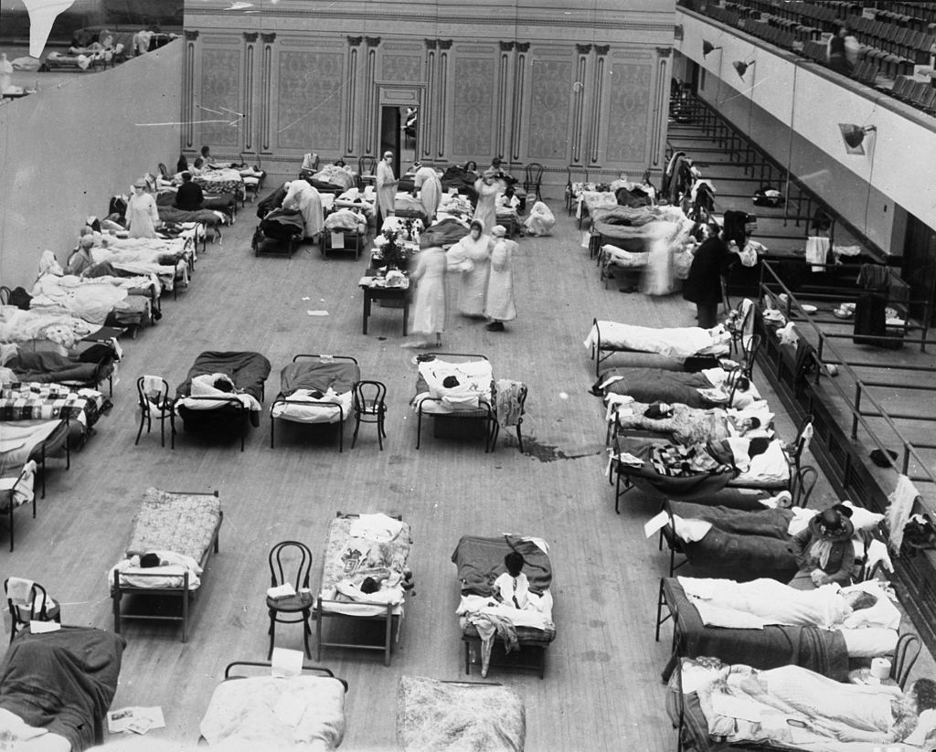

Photo by Edward A. “Doc” Rogers.

Many published histories of the 1918 flu pandemic concentrate on the devastation visited upon nations and populations. Most stop at the individual, because historians rely on tangible and verifiable facts, but literary fiction writers can turn personal narratives into stories that render pictures of what individuals could experience with particular illnesses. These two books referencing Pale Horse, Pale Rider in their titles—one a nonfiction history and the other a literary fiction—work well in combination to capture the experiences and consequences of this flu on both populations and individuals. Further, these two books show why fiction and nonfiction accounts of particular subjects should not be considered a choice, but rather as opportunities to get fuller accounts of diseases on populations and individuals.

Revelation 6:8, English Standard Version (ESV). © 2001 by Crossway; text edition: 2025.

‘Pale Horse, Pale Rider’ In The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter, Harvest, 1979.

Spinney L. Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World. New York; Public Affairs, 2017)

Web image generated by Gemini AI