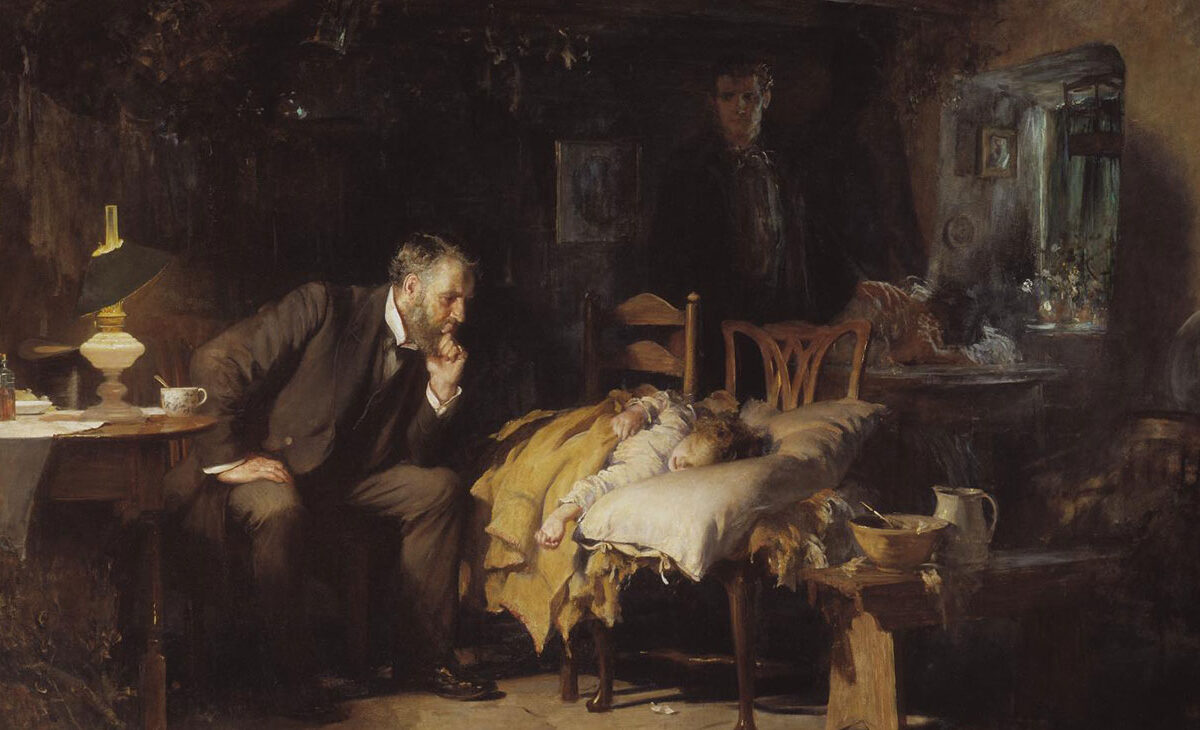

While visiting Anton Chekhov’s estate near Melikhovo, I purchased a reproduction of a late 19th century painting in which a doctor sits at the foot of a child’s bed in a darkened sick room. A second child plays on the floor. The physician speaks earnestly to the anxious mother, who stands beside him, wearing crumpled clothes and a babushka. Is the news good or bad? Will the boy survive? Whatever the outcome, this doctor appears to embody the best elements of traditional medical virtue. The scene is much like Sir Luke Fildes’ ever popular painting of “The Doctor” (1891). But the striking difference in this case is the man’s identity. The doctor in the Russian sickroom is Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, one of masters of world literature.

The artist depicts Chekhov as he was in the early 1890’s, soon after he had purchased a small, dilapidated estate and moved there from Moscow with his family. In addition to serving as country doctor and public health official in Melikhovo, Chekhov at that time was composing many of the stories and plays that made him one of Russia’s most well-loved writers and a major influence on 20th century literature. How was he able to pursue two such different and demanding careers? Several years earlier, at the height of Chekhov’s early literary success, his friend Alexi Suvorin had urged the young writer to give up medicine. Don’t spread yourself too thin, he said. You’ll never reach your potential unless you concentrate on writing. In response, Chekhov wrote, “You advise me not to chase after two hares at once and to forget about practicing medicine. Well, I don’t see what’s so impossible about chasing two hares at once… Medicine is my lawful wedded wife and literature my mistress. When one gets on my nerves, I spend the night with the other. This may be somewhat disorganized, but then again, it’s not boring, and anyway, neither loses anything by my duplicity.” (1) In this famous passage, the 28-year-old writer dances lightly over a fundamental truth of his life and identity. In fact, Chekhov’s career was not so much a matter of jumping from one bedroom to another, as was the case perhaps with the poets Wallace Stevens and T. S. Eliot, or the composer Charles Ives. Rather, Chekhov thrived on the effective, if not always seamless, integration of the arts of medicine and writing, which reinforced one another throughout his creative life. This essay explores that integration, and the manner in which Chekhov’s cold eye (objectivity) and warm heart (compassion) reveal themselves in his medical and literary lives.

DOCTOR CHEKHOV

“Medicine Is My Lawful Wife”

When he graduated from the Moscow State University School of Medicine in June 1884, Chekhov was already earning his living as a professional writer. The grandson of serfs, Anton was the third of six children in a poor merchant family from Taganrog, a southern provincial town on the shore of Sea of Azov. His father had moved the family to Moscow after going bankrupt in 1877. By the time Anton entered medical school on a scholarship in 1879, the Chekhovs were living in squalor. His father had a dead-end job. His older brothers were alcoholics and generally unemployed. Anton soon discovered that he could ameliorate the situation by selling comic sketches to local magazines for eight kopecks per line. This was a type of moonlighting he loved. He wrote obsessively, often knocking off a story or two each night, after spending the day listening to lectures or working in the hospital. Chekhov ultimately published more than 200 pieces while a medical student, most of them under his preferred pseudonym, Antosha Chekhonte.

Chekhov was a natural storyteller. Thus, it wasn’t surprising that the newly minted Doctor Chekhov continued to write, even after he opened his office and patients began to arrive. “Continued to write” is an understatement. Chekhov published 54 stories in 1885, 76 in 1886, and 57 in 1887. His work evolved from humorous sketches to longer, more serious stories for leading literary journals. In 1888 Chekhov won the prestigious Pushkin Prize and published “The Steppe,” his longest and most innovative story to date. Ivanov, his first full-length play, had a successful premiere in St. Petersburg in January 1889. By that time the young doctor had become one of the best known writers in Russia.

Yet Chekhov always saw himself as a physician, even though in 1889 he did, in fact, retire from a normal paying practice; after that, he offered his medical services at no charge, even though the generous Chekhov often found himself financially strapped. He took care of the peasants near Melikhovo (as depicted in the painting), donated his services to the government as a district physician, and engaged regularly in public health initiatives. In less than five months in 1891, Chekhov reported seeing 453 patients at a district health center and making 576 house calls, in addition to his home practice. (2) Throughout his life, Chekhov also was heavily involved in grass roots activism, building schools for peasants, raising funds to help famine victims, and, later, near the end of his life, supporting the establishment of a sanitarium for tuberculosis victims at Yalta.

“My Debt To Medicine”

One of the best known of these public health efforts was his 1890 epidemiological survey of health and social conditions in the prison colonies on Sakhalin Island. Traveling by himself, Chekhov journeyed six weeks by train, steamboat, and horse-drawn carriage across Siberia to reach the 1000-km long Pacific island on which the Czarist government had recently established a notorious gulag. There, he embarked on a one-man, three-month survey of the population, tenaciously picking his way from settlement to settlement and from house to house, often by foot.

Biographers have long tried to pinpoint his motivation for this perilous journey. During the year prior to the trip, Chekhov had undergone a crisis of confidence. In a letter to Suvorin, he opined, “I don’t love money enough for medicine, and I lack the necessary passion—and therefore talent—for literature. The fire in me burns with an even, lethargic flame; it never flares up or roars… I have very little passion. Add to that the following psychopathic trait: for two years now, seeing my works in print has for some reason given me no pleasure.” (3) He reported symptoms suggestive of clinical depression, perhaps precipitated by grief over the death of his brother Nicholas from tuberculosis. There was also a literary issue. The master of the short story had promised himself that he would create a Tolstoy-like novel that would confirm his status as a serious writer. But he was unable to do so.

Undoubtedly a major factor for choosing Sakhalin was Chekhov’s desire to pay his debt to medicine. He had recently developed a scientific interest in penology and had read about the dismal conditions in the Siberian gulag. He saw an opportunity to influence this situation by obtaining accurate data on the health status of Sakhalin convicts. He had never completed the research thesis (the equivalent of a Ph.D.) that would make him eligible to be a medical specialist or professor. Hence, his notion of “my debt to medicine”—he would perform a survey, write his thesis, and become a teacher.

Ultimately, Chekhov claimed to visit every settlement and survey every household on Sakhalin Island, using a 12-item data collection form. He said he completed over 10,000 of these forms in three months, a feat that (if true) qualifies Chekhov as the speediest shoe-leather epidemiologist of all time. After his return to European Russia, the author found it difficult to organize his data into a coherent study. While he had planned to write a strictly scientific monograph, his creative spirit struggled with the limitations of science. What about his personal experience? What about the interesting stories? After struggling for years, in 1895 Chekhov published The Island of Sakhalin, a curious (but engrossing) mixture of journal, geography, history, medicine, statistics, and travelogue. (4) Unfortunately, the faculty of the University of Moscow was unimpressed.

“As I Grow Older, the Pulse of Life in Me Beats Faster”

Picture the mature Chekhov—a middle-aged bachelor, longish face, rather neatly trimmed beard, a prince-nez clipped to the bridge of his nose. His household included his aging parents and his sister Masha, an unmarried schoolteacher who had become his confidant and secretary. His three surviving brothers looked to him for guidance and financial help. Anton was popular, witty, and generous. Among the guests at Melikhovo, there were frequently female admirers. Chekhov’s encounters with women were flirtatious and obviously enjoyable. He had teasing, sexually charged relationships with several women, but whether any of these liaisons are actually “affairs” is uncertain.

The doctor in the painting already suffered from the tuberculosis from which he would die at the age of 44 years. In fact, he first coughed blood as a medical student. Yet, Chekhov dismissed that episode and each subsequent episode that occurred with disheartening regularity as “influenza” or “bronchitis,” steadfastly refusing to label himself consumptive. As a physician Chekhov must surely have understood the meaning of his symptoms. Was his denial simply a face to show others? Or was his denial so great that it made him unaware? The cat finally came out of the bag in early 1897. While dining at a restaurant in Moscow, Chekhov had a violent spell of hemoptysis that left him critically ill. For the first time, he sought medical treatment and entered the clinic run by Dr. Ostropov, one of his medical school professors. Chekhov’s chronic illness progressively worsened. At the insistence of his doctors, Chekhov left his beloved Melikhovo after 1898 and lived mostly at a new home in the sunny Black Sea resort of Yalta.

It was also during these last years that the bachelor writer courted and married Olga Knipper, an actress with the Moscow Theater Arts Company. Even after their marriage in 1901, Olga remained at work in Moscow during much of the year, while the invalid Chekhov lived in Yalta, theirs being perhaps one of the earliest examples of the modern two-career commuter marriage. Chekhov found himself able to devote less and less of his waning energy to writing, especially since he refused to give up his social and philanthropic activities. Nonetheless, between 1898 and his death in 1904 Chekhov completed some of his greatest work, including several stories, two novellas (“Peasants” and “In the Ravine”), and his last plays, The Three Sisters (1900) and The Cherry Orchard (1903).

COLD EYE, WARM HEART

Chekhov’s Doctors

Several characteristics of Chekhov’s work reveal the influence of medical training and practice. He used clinical knowledge to lend accuracy to his descriptions of disease and medical situations. This characteristic is perhaps most clearly seen in the characterization of mental disorders. For example, the title character in Ivanov is a subtle portrait of a man suffering from clinical depression, who eventually commits suicide. The young heiress in “A Doctor’s Visit” presents symptoms we would now label as generalized anxiety or panic disorder. The title character in Uncle Vanya appears to have a neurotic depression, a condition that meets today’s DSM 5 criteria for Persistent Depressive Disorder. In the peculiar story called “The Black Monk,” Chekhov describes a psychotic condition, presumably schizophrenia.

Chekhov also drew from his medical experience in creating a multitude of physician characters. Doctors play significant roles in nearly 30 stories and in all of his major plays, except The Cherry Orchard. The author’s sensibility as a medical insider gives insight and poignancy to these characters, who range from committed altruists to lazy bureaucrats to burned out cases. Chekhov knew too much about the contemporary state of medical science to portray his doctors as curing many people. Thus, they often appear impotent. Yet, at their best Chekhov’s doctors convey the seamless fabric of tenderness (compassion) and steadiness (detachment) that lies at the heart of good medical practice. They also demonstrate courage, altruism, and self-effacement. For example, in “The Grasshopper” (1892) Dr. Dymov dies as a result of contracting diphtheria from a patient. Dr. Kirilov in “Enemies” (1887) demonstrates extraordinary devotion to duty by leaving his distraught wife and dead son in order to make an emergency house call.

Perhaps Chekhov’s most textured portrait of a good physician appears in “A Doctor’s Visit” (1898). The protagonist, Korolyov, is a young doctor substituting for his boss, the professor of medicine. During the course of the story he moves from being a careful observer (detached concern) who ascertains that his young patient has nothing wrong but a “case of nerves,” to making an imaginative leap by which he connects more deeply with her. This empathic connection allows him to relieve some of her suffering by re-framing her illness. While he cannot solve her existential problems, his demonstration of solidarity leads her to trust him and to gain insight. Korolyov is like Chekhov himself. Dr. Pavel Archangelsky, who supervised Chekhov’s first job as a physician, captured the author’s ability to listen carefully when he later commented: “… he did everything with attention and a manifest love of what he was doing, especially toward the patients who passed through his hands. He listened quietly to them, never raising his voice, however tired he was and even if the patient was talking about things quite irrelevant to his illness.” (5)

At the other end of the spectrum, some of Chekhov’s doctors are insensitive, incompetent, or impaired. Mayer, the callous medical student in “A Nervous Breakdown” (1889) is a disaster. Mayer can rattle off statistics on the number of whores in London and Moscow, but he is unable to “see” (empathize with) the suffering of the living-and-breathing whores he encounters. Shelestov in “Intrigues” (1883) and the public health doctor in “Darkness” (1887) are examples of self-centered physicians a little further along in their professional lives. The former is superficial and pompous; the latter is narrow-minded and detached.

Chekhov’s most complete insensitive and acquisitive social climber is found in “Ionych” (1898). Dr. Startsev, when the reader first meets him, is a young physician setting up practice in a provincial town. After surviving an unrequited infatuation with the daughter of a wealthy townsman, Startsev devotes himself entirely to work. His practice prospers and he branches out into real estate. As he grows corpulent and wealthy, Startsev loses touch with his patients (and his own humanity):

“Probably because his throat is covered with rolls of fat, his voice has changed; it has become thin and sharp. His temper has changed, too; he has become ill humored and irritable. When he sees his patients, he is usually out of temper; he impatiently taps the floor with his stick, and shouts in his disagreeable voice: ‘Be so good as to confine yourself to answering my questions! Don’t talk so much!’” (6)

“Ionych” traces the progressive destruction of a medical practitioner who finds that medical affluence is more to his liking than the emotionally and physically difficult path of medical virtue.

Some of Chekhov’s most interesting doctors are tortured by existential or spiritual conflict. Chekhov accurately depicted professional burnout, a syndrome characterized by depletion, detachment, depersonalization, denial, and depression. (7) Dr. Kirilov, who chooses to “go to the office” instead of mourning with his wife, may illustrate the relatively early phase of emotional detachment. Dr. Ovchinnikov in “An Awkward Business” (1888) demonstrates the more advanced symptom of depersonalization when he slugs his assistant in response to the man’s incompetence. The overworked Ovchinnikov reacts to his personal depletion by objectifying and dehumanizing his assistant, a response that compromises the medical care he is trying to protect. Chebutykin in The Three Sisters (1900) illustrates the extreme of alcoholism. Though still employed as a military physician, Chebutykin convincingly asserts that he has forgotten all the medicine he ever learned.

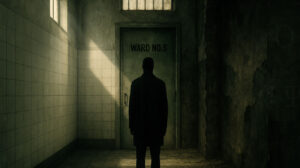

Ragin in “Ward #6” (1892) and Nikolai Stepanovich in “A Dreary Story” (1889) are complex characters in whom depression and burnout are superimposed on a deep sense of existential failure. Like many of Chekhov’s characters, these physicians suffer from a lack of self-knowledge; they move through life relying on one form of self-deception or another. When they were younger, they committed themselves to noble ideals—Stepanovich to teaching and Ragin to practice in a provincial hospital. But in the long run they never “found” themselves. Professor Stepanovich yearns for a unifying moral principle that would knit together the fragments of his life. Dr. Ragin experiences his failure as emotional numbness. He yearns to suffer, assuming that if he experienced pain, he would be freed from his inability to feel. Thus, the academic physician pines for salvation in the cognitive sphere; the practitioner yearns for emotional redemption. In each case the focus remains inward, rather than turning outward to others, in whom salvation might actually be found.

Medical Sensibility

Medical attitudes and methodology play a larger role in Chekhov’s work than does medical knowledge. He believed that his duty as a writer was to present his observations clearly and accurately; in other words, to lay out the data in an objective fashion and allow readers to reach their own conclusions, rather than providing an author’s interpretation. He wrote, “The artist should not be a judge of his characters and what they say, but only an objective observer.” (8)

This objective attitude put him in conflict with most other Russian writers of the time. It was a major source of conflict with Tolstoy, who was widely revered at the time as a living saint. The two men enjoyed a close personal bond but approached writing with radically different philosophies. After his mid-life religious conversion, Tolstoy viewed literature as a way to communicate his moral vision. He preached the gospel of a radical Christianity, in which all men work together to achieve economic and social equality. However, he rejected the concept of material progress and was particularly skeptical of medicine and doctors. Chekhov, on the other hand, strove to be objective, to present people as they are and the world as it is. His medical training taught him to be a careful observer; his medical attitude made him leery of judging others.

Other Russian writers and intellectuals spoke out against the czarist government’s repressive social institutions. While this protest was disguised in various ways in order to satisfy the state censors, late 19th century Russians (like their 20th century counterparts) learned to speak and understand a subtle code of insurrection. The intellectuals addressed “big issues”—democracy, education, social revolution. They wrote articles, organized meetings, and gave speeches. Here again, Chekhov found himself on a different wavelength. He rarely engaged in theoretical discussion and did not advocate radical social change. Rather, he preferred a pragmatic, case-based approach. His goals were relatively limited, but achievable. Treat the sick patient. Document and publicize the abysmal condition of prisoners. Contain the cholera epidemic. Provide financial assistance to keep farmers afloat during the famine. Raise money for a new school. On and on, but always specific and personal.

In “About Love” (1898), the narrator speculates on the essence of love. Are there universal characteristics that identify love wherever it occurs? “What seems to fit one instance doesn’t fit a dozen others,” the narrator concludes. “It’s best to interpret each instance separately in my view, without trying to generalize. We must isolate each individual case, as doctors say.” (9) Indeed, Chekhov’s stories and plays rigorously follow this dictum. While many of his Russian contemporaries used fiction to advance moral or social theories, Dr. Chekhov focused on the complexities of human interaction. In Chekhov’s world, biology and circumstance constrain freedom. People often do not listen. Acts performed with good intentions frequently result in hurtful outcomes. And yet occasionally and in unexpected places, one finds a glimmer of love, courage, spirituality, or healing. “Never generalize,” Chekhov tells his readers. “Never theorize. Pay attention to the particulars. Focus on the concrete.” In this respect, the 19th century physician-storyteller presages the 20th century physician-poet, William Carlos Williams, who coined the aphorism, “No ideas but in things.”

In the long run, Chekhov’s objectivity and aversion to theory played a major role in the development of modern literature, as 20th century writers followed Chekhov in attempting to describe the world of human character and relationship objectively, and allowing that world to speak for itself. To the extent that Chekhov’s “lawful wedded wife” contributed to his sensitivity, skills, and attitudes, perhaps medical education and practice played an unanticipated role in the history of literature, his delightful “mistress.”

Adapted in part from Coulehan J. (Ed.) Chekhov’s Doctors, Kent State University Press, 2003

Sir Luke Fildes’ “The Doctor,” is in the Tate: File:The Doctor Luke Fildes crop.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Chekhov: File: Chekhov 1898 by Osip Braz.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

REFERENCES

1, Chekhov A. The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov, translated by Sidonie Lederer, New York, The Ecco Press, 1984, p.

2, Coope J. Doctor Chekhov. A Study in Literature and Medicine, Chale, Isle of Wight, Cross Publishing, 1997, p.

3, Chekhov A. The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov, translated by Sidonie Lederer, New York, The Ecco Press, 1984, p. 81.

4, Chekhov A. A Journey to Sakhalin, translated by Brian Reeve, Cambridge, Ian Faulkner Publishing, 1993.

5, Coope J. Doctor Chekhov. A Study in Literature and Medicine, Chale, Isle of Wight, Cross Publishing, 1997, p. 27.

6, Chekhov A. Ionych. In: The Tales of Chekhov. Volume 3, translated by Constance Garnett, New York, The Ecco Press, 1972, p. 91.

7, Coulehan JL. Being a Physician. In: Mengel MB, Holleman WL (Eds.) Fundamentals of Clinical Practice. A Textbook on the Patient, Doctor, and Society, New York, Plenum Medical Books Company, 1997, pp. 73-101.

8, Chekhov A. The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov, translated by Sidonie Lederer, New York, The Ecco Press, 1984, p. 54.

9, Chekhov A. About love. In: The Tales of Chekhov. Volume 5, translated by Constance Garnett, New York, The Ecco Press, 1972, p. 290.